Share this Post

PUBLISHED

February 27, 2020

WRITTEN BY

Adrian Bartha

A colleague of mine, let’s call him Mark, once came into my office and announced he was officially ready for his first role in managing a team.

He was a top performer and it was a bold choice which I admired, but I felt uneasy about his proposed position. At the same time, I didn’t want to take the wind out of his sails, as he clearly displayed great leadership qualities over the last 12 months. As I was thinking about it later that night, I wondered why I didn’t feel confident in his transition to management. I honestly didn’t think he would enjoy a management role as much as he thought he would, and it got me thinking: why would someone with great leadership skills not be an energized and successful manager?

There are a million books on management and leadership out there, and most of them can be quite dogmatic. Yet the question on the distinction between management and leadership is often overlooked. I need both qualities in an effective manager.

A colleague once gave me an engineering booked called The Art of Scalability. The book has separate chapters on management and leadership which highlight the important distinction between each. It defines leadership as “influencing the behavior of an organization or a person to accomplish a specific objective”. In other words, you don’t need to be a manager to be a great leader. However, being a great manager requires building up skills and having a keen eye for several things that may not be obvious to someone who is getting into it for the first time (myself included!).

“Management and leadership differ in many ways, but both are important. If leadership is a promise, then management is action. If leadership is a destination, then management is the direction. If leadership is inspiration, then management is motivation. Leadership pulls and management pushes. Both are necessary to be successful…”.

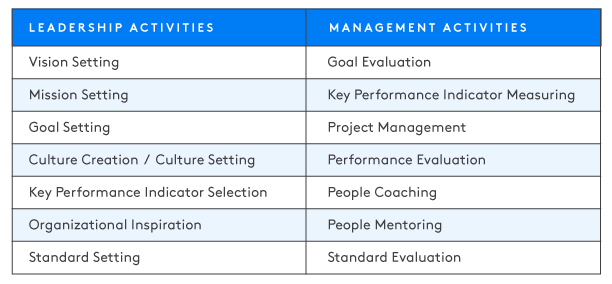

The contrast looks like this:

So, did we promote Mark? Yes and no. We first wanted him to dip his toes into some of the management activities above. The reason for this was two-fold: we wanted to give him a chance to see if he would actually like it, and we wanted to provide him with an opportunity to gauge if he was ready for this role at this stage in his career. We decided to give Mark responsibility for half of the activities above for 3 months to see how he liked it. Ultimately, he came to appreciate how the energy that gave him those awesome day-to-day leadership skills was not the same energy he would ultimately feel when working to be a great manager at this point in his career. However, it did give him a roadmap of things to work on if he wanted to become a manager in the future. It also enabled him to embrace leadership in his team and across the organization in a way that was not formalized but still recognized and valued.

Mark didn’t “fail” in his activities above, but rather we saw it as a test that would go one way (or another), and the organization would be better off irrespective of the result. How do we create that safe place for leaders to discover themselves or try new things?

In the article “Redefining the Role of a Leader in a Re-skilling Era”, one management guru points out “The leaders I see who are really building an organization …are those who not only are honest about their own failings but also create an environment of psychological safety for their employees so that they are comfortable making mistakes as they learn.” HBR discusses this further in the article, “Hire Leaders for What They Can Do, Not What They Have Done”. This piece reinforces the message that most promotions happen when we’re looking backwards at past performances. However, it is more effective to try to predict the future state of the organization considering uncertainties and changes, and make decisions regarding promotion this way.

Reflecting on our situation with Mark and my own instincts on the matter, I realized the real reason I was unsettled about promoting him was not because of his lack of experience but because we didn’t create a psychologically safe place for Mark to try management out. But when we did, we learned it was not the right time for him and this was critical for Mark (and other future leaders in our organization) to know. It was not out of a lack of experience because we’re all first-time managers at one point or another. The communication on this particular point to other employees was crucial and was admittedly awkward at first. However, it paved the way for future dialogues with colleagues on the management career paths in the company.

What are some ways you’ve created a ‘safe place’ for leaders to thrive (or even fail)? Is it deliberate or accidental?

Do you have managers that are poor leaders or great leaders who would be poor managers? How does this distinction come out in performance reviews or professional development discussions?

Rethinking Safety

Drive employee engagement by connecting

your frontline to your boardroom.

How Turner Construction improved worker participation by working on continuous improvement

READ CASE STUDY